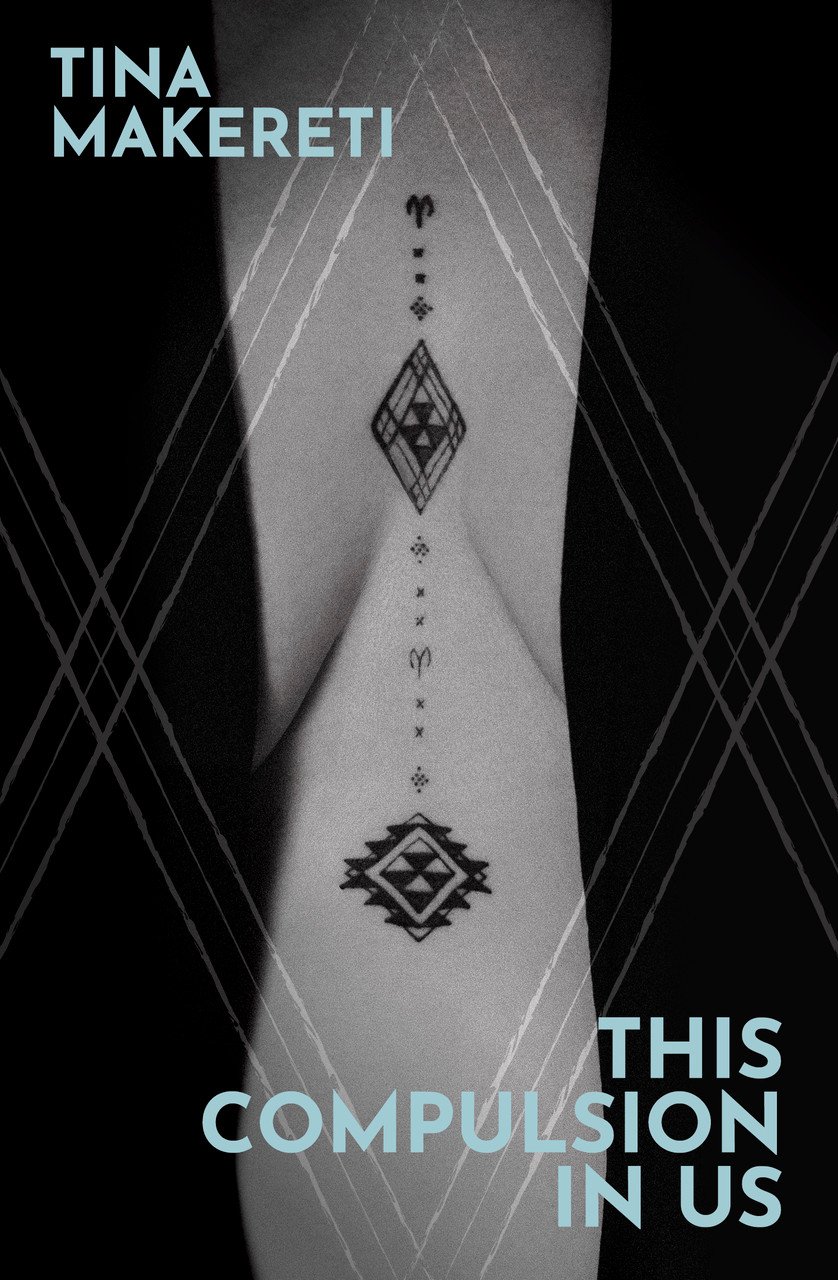

‘This book opens up the world—the gritty, hungry, paradoxical world. Like the best essayists do, Tina opens her world to us in the most personal of ways, then out and out again so that your view is much much bigger than when you began.’ —Tusiata Avia

‘Her name reminds me when to be careful, and when to take risks. Her name keeps me safe.

In This Compulsion In Us, Tina Makereti takes many risks; the writing is a skilled yet poignant navigation of the “choppy, dark seas of identity loss and searching”. It is a compelling read: a provocative mix of notable essays that consider what writers do and what she does, blended with sections of refined and reflective memoir. These chapters are coloured by a sharply unconventional upbringing, her reconnecting with her Māori mother and beloved grandmother at sixteen, and her life as a young mother living overseas. She is guided by ghosts, inspired by memories and affirmed by tīpuna, by an ancestral presence that consistently reinforces her creative work. Her fiction sings with their voices; this new book describes where they come from, how they manifest, inspire and protect.

‘What pervades This Compulsion In Us is the power of imagination, the impact of story, the motivation to grasp, examine, and release. Writing, in itself, is an act of defiance and bravery. Tina has the courage to write what scares her, to put it all out there, carefully, eloquently, and by doing this she makes sense of so much. And she offers this to the reader, asserting that writing is healing and retaliation, discovery and exposure. Taku taina, tēnei rā taku mihi aroha ki a koe; mā te pene, mā te tuhituhi, ka piri pono ai, ka hono tahi ai, ō tātou wawata.'

—Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku, Kohitātea 2025, Te Kuirau

It’s not beautiful, not at all, when it’s there in front of you, but writing transforms.

In her first book of nonfiction, prizewinning author Tina Makereti writes from inside her many intersecting lives as a wahine Māori – teacher, daughter, traveller, parent – and into a past that is as alive and changeful as the present moment.

Makereti stands at the foot of her mounga and pays careful attention to tohu. With her tūpuna at her elbow she casts around for home, meets taonga in museums, and writes her way towards her father. She walks through the darkness with others, in awe of Te Kore, Te Pō and Te Ao Mārama—a universe of potential being, dark and light. These are some of the kaupapa that underpin her work and her way of moving through the world, both enlivened and haunted by a compulsion to write.

Included here are frank and moving essays about the wāhine who have shown her many ways of being a Māori woman, the pain and dark humour of living with an alcoholic, a blue boob from breast cancer treatment, and the potential of art to return power to survivors of colonialism. What if we could transform the events that made us who we are? What if there were a way back to the beginning? By turns lyrical, personal and critical, This Compulsion In Us is many things all at once, and an unforgettable portrait of one of Aotearoa’s foremost storytellers.

‘This is such an important book. Beautiful. Completely compassionate, utterly necessary.’ —Ingrid Horrocks

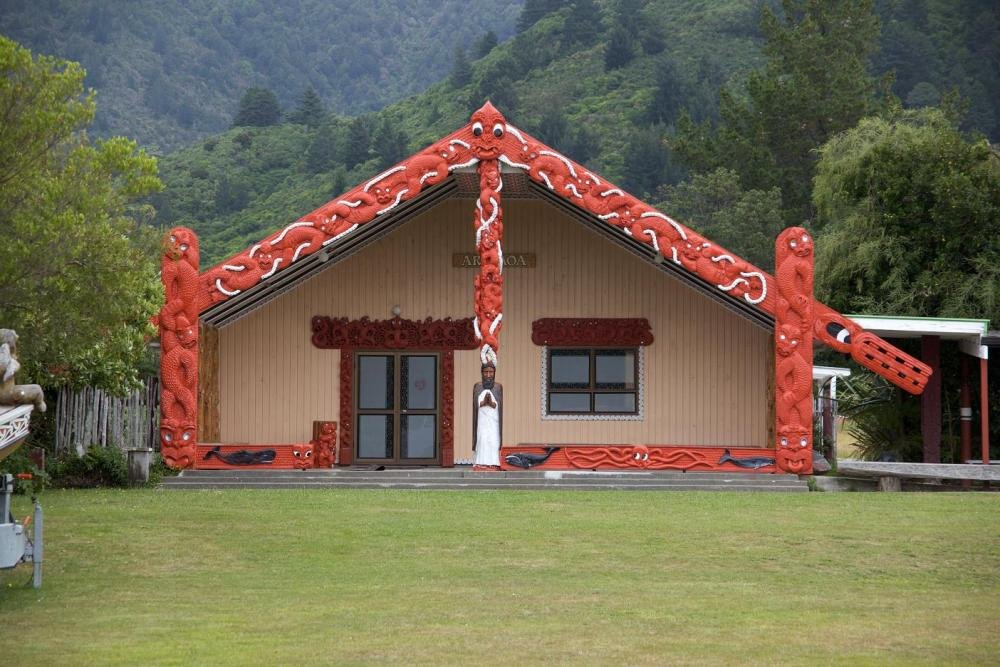

Waikawa Marae

Poutokomanawa - The Heartpost (2017)

I want you to think about what you would like to see at the heart of your national literature. I know that my literary poutokomanawa begins deep in the lands and seas of Aotearoa, where the stories of this country began, eons ago, and that even then our whakapapa connected us to the entire Pacific. I know that eventually our stories became inextricably linked with another culture from far away, and then more. I know that what makes us strong is this story, not of an inherited English literature, but of the extraordinary mix of language and narrative and metaphor that could only take root in this one place on Earth.

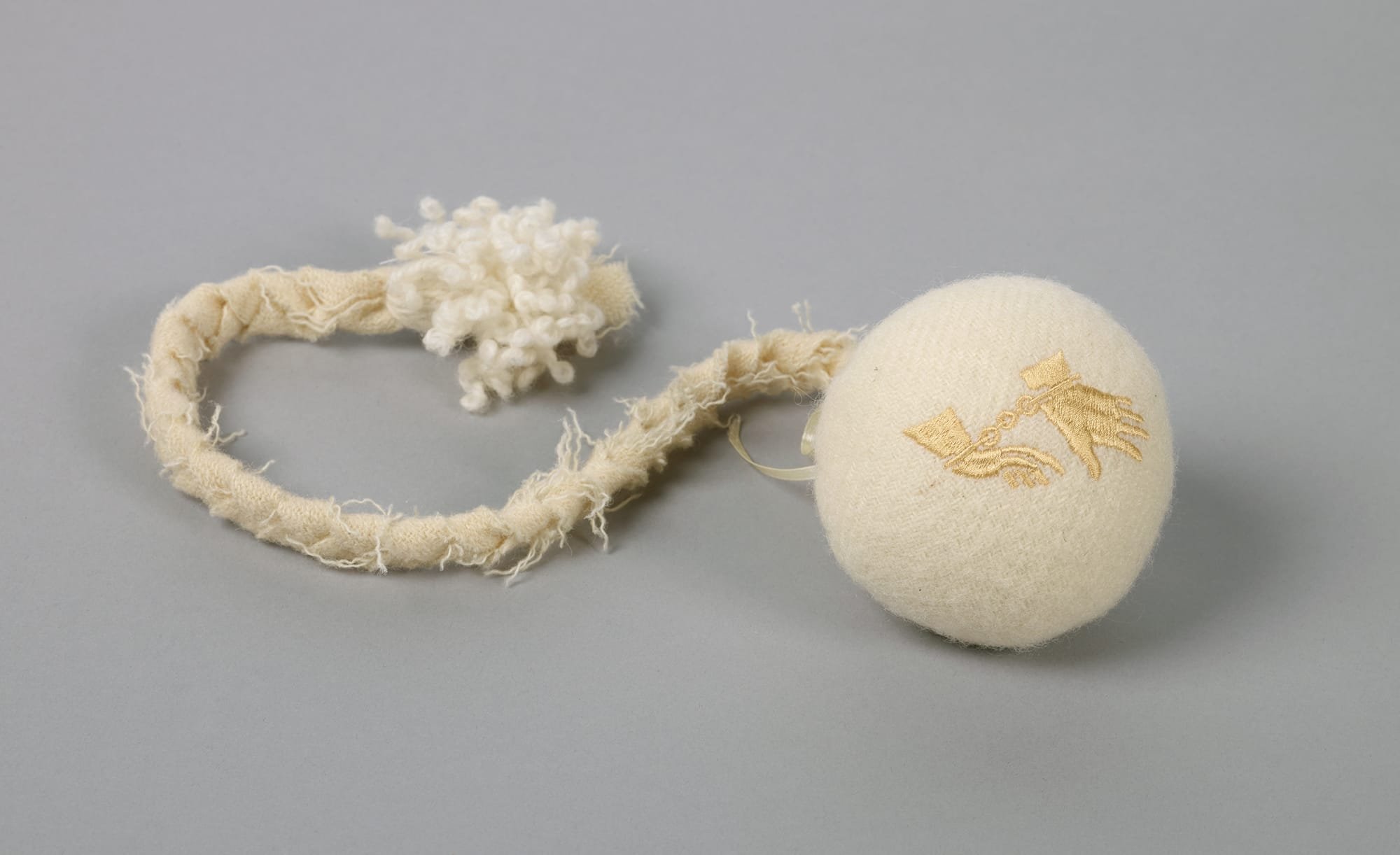

Poi by Ngaahina Hohaia, circa 2009. Gift of Teina Davidson to Te Papa, 2012 (GH017810).

Pao Pao Pao (2018)

I grow out of those goddesses you've heard about: Papatūānuku, Hinenuitepō; goddesses who were grandmothers to my grandmothers. When everything is whakapapa, those women become more than archetypes. I can look at my own flesh and see their DNA, listen to the laughter of my daughters and hear their voices. The real world exists at this level. Any understanding of women's power, for me, is derived from this deep soil. Women run families and nations and always have. Men work alongside them in these tasks because they always have. At the centre, the children. To disregard the unique abilities of any one group in this community would jeopardise survival. Everyone according to their strengths.

By Your Place in the World, I Will Know Who You are (2016)

Sometimes, writing a personal essay feels like a constant argument about place — the place I belong, how I place myself, my place between cultures — a constant wrangling between two sides that at its simplest is embodied by my Māori and Pākehā parentages… The essay is the perfect site to explore paradoxical questions because an essay is supposed to be nonfiction, which means it is supposed to be about a knowable truth. And yet the essays I enjoy circle around the unknowable, constantly trying to place a finger on what something is, constantly searching for answers to questions the writer knows are, at some level, unanswerable.

Tūpuna, Te Awaiti, Arapaoa Island, 1890s

An Englishman, An Irishman and a Welshman Walk into a Pā (2012)

Of course, like many good stories, this one touches on the challenge of prejudice, the mediating power of sex, and the triumph of mythology. From the first I was made aware that I came from two peoples, and that these two peoples had a lot of unfinished business to attend to… What made me interested in the stories of my Pākehā Māori ancestors was this: if we have been intermarrying since earliest European contact, and if our earliest white ancestors in New Zealand were willing to approach their ethnic identity in a fluid and adaptable way, why wasn’t the development of New Zealand culture more representative of the experiences and approaches of these men?

Calabash International Literary Festival, Jamaica, 2016

Bleeding on the Page: On writing, community and reviews (2020)

The saying goes that to be a writer all you need to do is sit down at the typewriter, open a vein and bleed. And the longer I stick around, the more I believe that’s true. It’s not worth anything unless you risk everything. The really good writing is always the stuff you’re scared to put out there, the stuff for which you imagine you will pay at some point. That’s the stuff that readers come and talk to you about, the stuff that connects to real pain in their lives. It’s not the most important job in the world, but it takes a fair bit of courage and foolhardiness, and it matters.

Illustration by Caleb Carnie for Sunday Star Times

Dog Love - a short [true] story amid covid19 lockdown (2020)

She's a snuffler, a cuddler, her Staffy-Vizsla-Whippet genes priming her for play and affection above all things, a wiry ginger ball of neediness… Now it's just us and her, and sometimes that unnatural bark, pre or post-cursor to naughtiness, acting out, distress. She stares then, straight into our eyes, and her confusion is clear. What the hell is going on? She can't say it in words, what she needs, but she's unsettled by all the changes, by our behaviours and feelings, so many feelings, which are all as clear to her as the thousands of smells that she can detect and we can't. Dogs are all sense, all feeling, body language, smell, sound. She knows exactly how we are, more than we do most likely, but what's she supposed to do with all that? What does it mean to her small muscular body? Tension without release.